We were driving down the roads of childhood, though it was now I who cradled him under my arm. My father’s urn bore his name in gold on the lid: Claude Courchay 1933-2024. What is left when a writer dies?

The question doesn’t suggest the gears of ceremony and bureaucracy set in motion by the demise, the particularities of each passing, the longer or shorter trips, the numbers of obituaries, flowers, and mourners at the burial or cremation. It stems, instead, from an idea that came to me with another death early in life, at the threshold of a room untouched since the person left it for the final time.

Inside that room, I had felt, was a momentary suspension, an order that would soon change, but which for a moment yet retained what then seemed invaluable: the morning’s discarded shirt, a fold in the bed sheet, a list on a notepad…a series of mostly thoughtless, even banal motions, that remained as the final strand in that long series called daily life. From then onwards, every action taken in that room would be the undoing of the last gestures of a loved one.

That was long ago; it was a different loss at a different age, though from it, I retained, for the present, the premise of retracing what I could of my father’s life based on what I saw inside his small apartment, in the quaint Provençale town where he’d spent the year since his health had declined.

I left the urn on his bed. The apartment was a rental and needed to be emptied with enough haste to leave musings on the shorter side. He made it easy for me, and throughout the next days, as I undid, unfolded, packed, or discarded everything in sight, that question came, though it wasn’t a question but the silent statement made of all those things I saw, touched and to which I bade goodbye. As any individual, he was many things at once, yet his vocation seemed ingrained in even the smallest traces I found.

In reopening his apartment, after his death, the priority was to deal with his estate, and hence I went looking for papers, insurances and contracts. A paper trail to fix the mess left behind. There was none of that. There were, on the other hand, notebooks, letters, pages full of quotations, and the manuscript of a book in perpetual gestation.

There was what is left when a writer dies:

A broken mug on the living room table, full of pens, with the outline of a gun that reads “Murder Ink, The Mystery Bookstore,” which once graced Manhattan’s Upper West Side and which spoke of his passion for the genre, of which he’d been literary critic, then a prolific author.

Beside it are fragments of a work in progress: a single page, nearly blank save for a dedication to La Princesse de Clèves, the title and titular character of an XVII century French novel. A companion piece is nearby. Handwritten, it indicates a chapter on the left hand corner (23), and a page number on the opposite side (81). The first line reads, in French: “Back to earth, then. Fair weather, overcast. Life stutters (crossed out). That exit! Three steps in the clouds.”

Nearby lay a selection of newspaper clippings, to share because they caught his eye: An article on the harrowing story behind Degas’ statue, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen; the account of an attempted murder by sword in Marseille; an opinion piece (underlined) on the decline of culinary habits of France.

On the bench next to the table, a pack of 500 white pages, on which he wrote after his last typewriter died.

A brown envelope lies by its side. The sender’s address belongs to a friend in a nearby city. The envelope is open, inside are three articles with his son’s byline.

There are also three dry roses in a vase, added here for no reason other than I remember how he would sing when he cut them in the yard.

On the half wall separating the kitchen and living room, a series of letters from one of his readers, recounting the time he’d driven to my father’s isolated town to share a handshake, which had left the recipient dumbfounded (“On top of writing my books, do I also have to read them? I don’t remember what they’re about!”)

Downstairs, on the desk, a postcard of Hong Kong in 1997, the year of the handover from the UK to China, to which he’d traveled with his friend Michel Setboun, a photographer for National Geographic.

Above the postcard, on a shelf carved into the wall, there’s something approaching his complete works. Most notable are the old editions of his first six autobiographical books and a single paperback of his lone bestseller. Add two or three of the most egregious covers bestowed on his later novels, so abhorrent he couldn’t bear to part with them (for fear someone else might see them, he’d add).

In the drawer, his author royalties for January 2021: 0,95 euros.

On a low dresser was a folder with an assortment of loose pages seemingly ripped from various notebooks. Some barely a couple inches in height, scribbled throughout; a series of numbered pages with the ink faded by water; his Cambodian driver’s license; a letter from a lawyer from 1972; a yellowed article from 1978; paragraphs written on the back of a square of paper with the logo of the Gallimard editing house, on the back of a 1977 receipt from the Sandpiper Lodge in Santa Barbara, CA.

A compilation whose meaning no one will ever figure out.

Then, in a bag near his bed, various items. There is a diary for the years 1996-2000, in red and black binding, from which a more recent entry falls out: a rejection letter from an editor dated May 7, 2021, stating “Madam, thank you for sharing your book project (...) the reading committee has rendered a negative verdict.” Alongside is a notebook of the type used by schoolchildren, in an unknown handwriting, full of quotes ranging from Nietzsche to Baudelaire. Two black and white portraits of a woman are slid between the covers.

Also: Three full manuscripts in separate folders, two by hand, one typed.

A writer died on February 8th in a local hospital in the south of France. He stopped breathing around 2 am, local time, due to Covid, like too many have. His casket, in the funeral parlor, was advertised under the name of a mountain that he could see from his home. There remains an apartment full of books and flotsam. The former structured his life and lined the space above the pantry, overflowing and threatening to plunge onto the pans. Of all the questions I’d ask, the one that stays at the forefront is: what did he read last? How far into the book before the oxygen mask?

I know he wouldn’t go anywhere without something to read; he couldn’t, not even on his deathbed, he never has. Yet at the hospital that day, the staff gave me only an old blanket, telling me that’s all he had brought. I know that’s not right. I seek out the village nurse who found him lying on the floor that morning in his flat. She tells me on the phone that she packed his things and there was a book, she saw to that. So I insist and the hospital admits they misplaced it, they’ll call me if they can find it.

Does it matter? In his house, there are so many other volumes to package. I’ve never met someone who read quite like that. Ceaselessly, well past midnight. If I remember outward shows of tenderness, I remember kissing him good night, on the forehead, with his glasses on the bridge of the nose and the open page on his knees, most often with his chair rocked back, feet on the table, in that tilted balance that I’ll always associate with that act: reading on while I slept tight. Maybe there’s one book to conclude his lifelong reading list, and maybe there’s a bookmark inside, a sign to know the last words met by eyes that lived to greet the page, something to make up for never reaching him at the hospital, for all the imperfect goodbyes.

I go to his local library with a shoebox full of what I found. The kind lady at the desk tells me what he’d checked out for the winter. It includes a lot of crime novels by James Ellroy, Lawrence Block, Phillip Kerr, Jo Nesbø (which he didn’t like), but also two historical books on the Dreyfus Affair, The Catcher in the Rye as translated into French by one of his friends, and a book he never returned, which isn’t among the ones I’ve brought back. It’s Anna Karenina, by Tolstoy. So I insist at the hospital.

No, there’s nothing else, they say. Yes, they’ll look again. After a few skirmishes, a miracle: his things are found. “Please come and pick them up when you can.” Once there, it’s all in a plastic bag, containing his glasses, his wallet, his watch, and the book at his bedside.

There’s a bookmark lodged at the beginning of the second part.

There’s a handwritten phrase on it.

It’s a play on an old French aphorism:

“Every hour counts – the last one kills.”

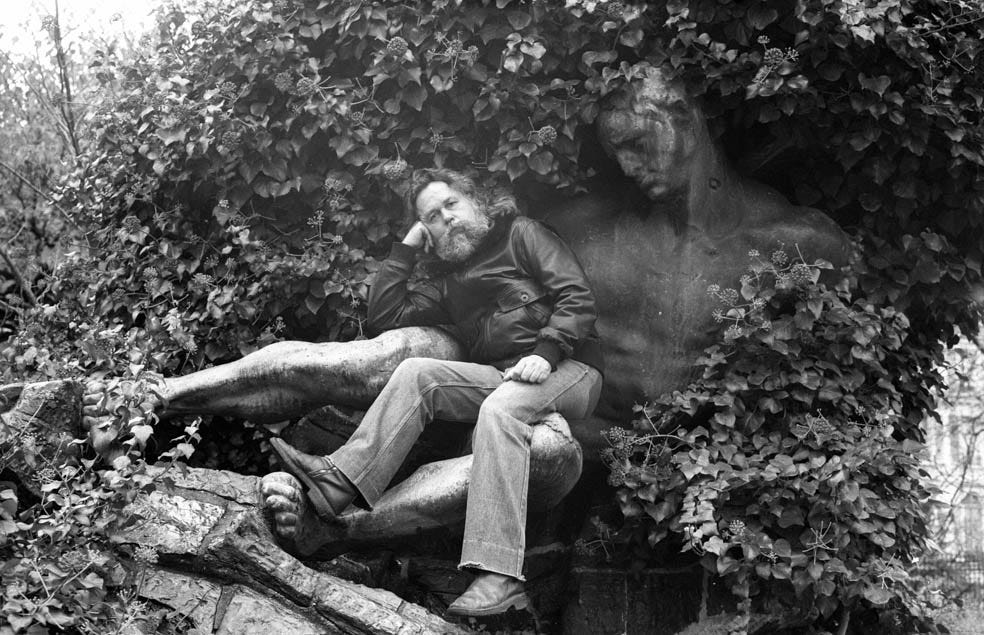

Portrait of Claude Courchay by Michel Setboun

* * *

Nothing good ever came from writers punishing themselves. We know writing is hard. We’re here to show that it doesn’t have to be torture. Writerland, The Delacorte Review Newsletter comes out every week.

This is touching, beautiful writing.

Rest in peace to your father.

Dear Diego: Your lovely description of your findings at your father’s appartment and later at the hospital are moving. In search of clues to learn about his last hours, the triggering of his writing. A sober recount worth reading. May he rest in peace.