Chapter 163: Cracks and Ghosts After the End of the World

In writing, brevity brings difficulty. As Truman Capote attested, “When seriously explored, the short story seems to me the most difficult and disciplining form of prose writing extant.” The precision it entails, the apparent clockwork-like unfolding of the narrative, leaves little margin for error. This has often led to its reduction to nuts and bolts, to be studied and reproduced, distilled into a long line of rules, formulas, and corsets of varying utility. Many stories are written thus, with the smell of test tubes, forgotten as soon as they are read.

It’s a particular form of relief to rediscover exceptional short stories: they remind us, amidst it all, why this genre is often the gateway to loving literature. Which leads us to Bolivian short story writer Liliana Colanzi (Santa Cruz, 1981), who, in two collections – Our Dead World, You Glow in the Dark– brings back the utter wonder and strangeness that can exude from a few tight pages. Colanzi teaches Latin American Literature at Cornell University, and you can read her work in The White Review and the New Yorker.

DC: In your literature, there is a mixture of singularity and universality. Among the first are the national elements, the deeply Bolivian worldviews, elements and words. How do you write from the singularity of a country so that your narrative can touch anyone?

LC: The stories do not emerge as an idea to say something about the country or its political or social reality, although they certainly do that, too. Many of these stories came out of a curiosity or a desire to move toward places I felt were a bit abandoned by literature. The narratives of the last decades are very focused on urban life, where most of the population has moved. But I felt there was something very interesting to explore in the countryside and our relationship with nature. The countryside is where those of us who live in the city draw all our comfort, our food, the raw material for everything, all the industry. It is that place to which we don’t usually grant two minutes of thought. It was fascinating for me to go back and explore what happens there, because this is also the place of extractivism. Some of the stories in Our Dead World have to do with what happens with that Indigenous world, which is also related to the rural world, which does not necessarily have a voice or which, in many cases, survives only in a ghostly way. And what do we do with that ghost that returns and returns, which we try to silence or ignore but which haunts us like a little voice in our heads, like an annoying buzzing? What has happened to that story? And that is how that voice filtered into many of the stories. The relationship with nature, the animals, and everything being destroyed as a certain idea of progress enters the countryside also interested me.

It also seems to me that there is a lot of poetry in the words that come from the indigenous languages or even from the modifications of Spanish that are particular to each region. There is a musicality and also poetry in these terms. One example is in “Meteorite,” with the use of Q’encha, an Andean word for bad luck. I was interested in recovering these terms. I don’t necessarily know from which indigenous language they each come, and that also caught my attention; it made me ask myself what happened to those people who have disappeared and of whom we only have a word or a couple of words left. And this is the singularity of Bolivia, where so many peoples and so many temporalities coexist at the same time. That layer of multiple coexisting times was fascinating to explore.

DC: Your stories tell of profoundly human terrors, daily terrors, and everyday violence, which in your literature are rediscovered obliquely through fantasy, horror, and science fiction. I wanted to ask you about this constant uneasiness in your stories.

LC: The book’s atmosphere stems partly from the long winters in Ithaca, in Upstate New York, where I live. It’s a six-month winter in a fairly isolated, small town, in a college town. “Our Dead World” tells of a woman who is a colonist on Mars and of a sense of isolation taken to the extreme. My move to the United States, my migrant experience, has a lot to do with Ithaca, with its long winters and also with a brutal period of insomnia that lasted a couple of years, which for me was also an experience very close to madness, to the loss of reason. Because when you stop sleeping for an extended period of time, reality blurs. And that was the atmosphere that seeped into all the stories. There is an approach in each story, in different ways, to what would be an experience of senses on edge, an alteration of the senses presented in various ways: from the almost mystical experience of psychosis produced by drugs in “Meteorite,” to the loss of reality from complete isolation due to migration to another planet, as in “Our Dead World”; to the religious experience in “The Eye”; to depression, in “The Wave”. I wanted to get close to these states, in which reason gives way to another approach to reality.

DC: In the story “The Wave,” there is something almost inexplicable. The reason that story works is not only because of its form or because of perfect mechanics. You seem to write some parts in a trance or driven by a very strong emotion.

LC: That story came to me in images. I didn’t necessarily know what it was about. I was asked to write a story about the Apocalypse, because it was then 2012, the year the world was supposed to end. The first image that came to my mind was from that same year, a few months before, when a cab driver picked me up at 04:00 am from the airport to take me to my home in Santa Cruz, and he was telling me on the way about how he had become an evangelical. He told me that, one night, he had turned on the TV and had seen a cholita, an indigenous woman, telling how she had visited heaven and hell. And then this cab driver gave me a very vivid account of all the things that this cholita preacher had said about what was in heaven and hell and even gave a list of politicians who were in hell. We had a very long conversation with this cab driver at 04:00 am, in the dark, while he was taking me home, which is a long way, and he even told me the date the world would end, which was to happen at some point in December 2012. That is to say that we are living after the end of the world, and maybe all this is a dream in the aftermath, at least according to this cab driver. From that idea, I began to link other images that I found powerful but that weren’t necessarily related to each other. For me, it was important to conjugate something dark, which came with that wave, that image of a devastating force, with something luminous, which was the counterpoint of this mystical cholita.

DC: Our Dead World and You Shine in the Dark have echoes and similarities, but certain searches accentuate over time. If Our Dead World owes a lot to insomnia, what atmospheres were developing these later stories?

LC: In Our Dead World, the characters, for different reasons, find cracks in reality: there is a child who comes back from the dead, an alien presence in the jungle, a supernatural wave on a university campus, an evil eye that pursues a very religious young woman. In You Shine in the Dark, what is rarefied or defamiliarized is time: “The Cave” attempts to capture geological time, insect life, mutations, and what the passage of time does to the planet and human beings. But the stories are also attempts to excavate past events and bring their power or their ghost to the present, and even try to imagine a future from that historical sediment: “Atomito” is inspired by the Taki Onqoy, the anti-colonial movement that occurred in the Andes in the sixteenth century, and “The Debt” takes place in the ruins of a town that lived through the rubber extractivist boom.

DC: Your stories create a variety of worlds, close and dissimilar. One constant is the narration from or about the periphery, whether it is the periphery of modernity, the periphery of society, the periphery of development, or of those who feel marginalized because of the color of their eyes or the narrow religious beliefs that govern their lives. Why does that perspective matter, and what does it bring to your stories?

LC: Periphery is a matter of perspective. For the global North, we are the periphery, the garbage dump of the West: recently, a Trump campaign speaker said very unabashedly that Puerto Rico is an island of garbage. This idea is as harmful as the one that demands the Global South to be the repository of purity and innocence. Latin America is a political and intellectual laboratory in which very interesting and, of course, contradictory projects for the future are being tested: the world has much to learn from the environmental, feminist, and popular struggles of the region. We are alternative centers rather than peripheries. In my stories, there are several historical layers in tension: what is anti-modern in my stories are not the rural settings or the characters living precariously, but rather the colonial, racist, and patriarchal substrate in which we continue to live.

DC: One element of your literature is the intertwining of grim modernity and a living, if often unrecognizable, past. Here, this exploration is allied to that of various genres: you weave together fantasy, horror, futurism, and dystopia. Tell me about your interest in these genres and the possibilities they present.

LC: I went into the fantastic because realism was no longer enough for me to talk about individual and collective trauma. Our Dead World is a book of ghosts, and by definition, the ghost is the symptom of a trauma that has not been socially recognized, so it comes back to bother the living until given its place. The horror genre tells us that the past is not gone, that it continues to act and cast its shadow on the present, and that it can even permeate –or rather, haunt– a physical space with that negative charge. Horror allows me to delve into intergenerational traumas and the wounds of history. Science fiction wonders about the future, which is an increasingly disturbing scenario because of the horrors we are subjecting the planet to; for that very reason, I think science fiction is the ideal place to ask important questions about what the future might look like, with its shadows, challenges, and resistances.

DC: “You Shine in the Dark,” the title story of the book, tells of the radiation contamination of a city amid innocence, incomprehension, and irresponsibility. Ultimately, we discover this is based on something that occurred in Brazil in 1987. Was it a different process to work with a historical event?

LC: Generally, my writing works by free association (I don’t take notes, I listen to the text to hear where it’s alive, and from that intuition, the story takes one direction or another), whereas the process in this story was different because I had never worked so closely with historical facts before. Obviously, the story is completely traversed by fiction, but I did not make many changes to the facts of how the radioactive accident occurred and the fate of some of the immediate victims, as well as the corollary of the disaster, which meant the demolition of dozens of houses in Goiânia, the displacement of those affected to other areas of the city and the construction of a nuclear cemetery to house the waste. In the first versions, the story had a more speculative side that I later discarded because I realized it was superfluous: the facts were already frightening enough without adding some fantastic element. I have always been interested in radioactive contamination accidents because of their enormous destructive capacity. I was surprised that one occurred in Brazil and was scarcely discussed.

* * *

If you have a question, a problem in your work, if you are feeling lost, stuck, confused, at sea, searching, grappling, or baffled, email me at Michaelshapiro808@gmail.com and tell me what you’re confronting and what help you need.

It is seldom, if ever, the case that one student’s problem or question is their’s alone.

Please indicate if you want to remain anonymous, have your name or just first name included. I will include the question and then answer it as best I can.

* * *

Nothing good ever came from writers punishing themselves. We know writing is hard. We’re here to show that it doesn’t have to be torture

* * *

We’ll be off next week for Thanksgiving. See you on December 6th.

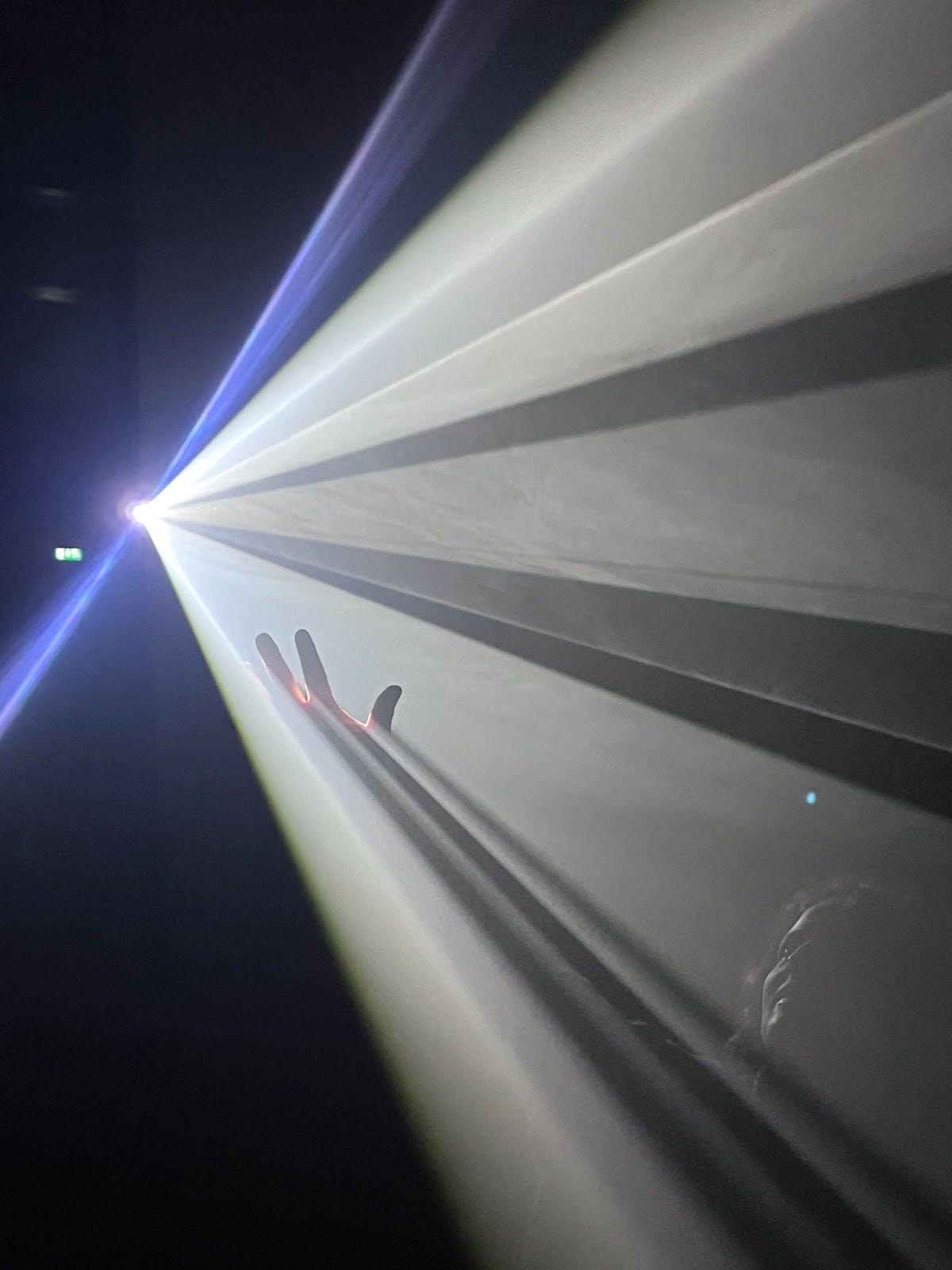

Photo taken at Solid Light, Anthony McCall, Tate Britain