Chapter 169: Internet Orphans

Of my many, many fears in anticipation of launching our publishing venture, The Big Roundtable, the one that most vexed me was the prospect of sending into the ether stories that would, in effect, become “internet orphans.” By this I mean stories that once published would be left to drift through the online galaxy, alone, unnoticed, and unread.

It was all well and good to celebrate the fact that the digital age made it possible for anyone to become a publisher. But the great disruption had not made all those legacy publishers vanish, leaving the field and all those potential readers to upstarts like us. There was us and them and all those readers whom we hoped to convince to turn our way.

We were confident in our ability to help writers; we had spent our careers writing and editing the very kind of ambitious narrative nonfiction we were publishing. But like so many other journalists who had come of age in the old order of the analog world, we knew very little about readers – their habits, wants, behavior and desires.

In my mind, readers existed in the universe like neutrinos – the small and most ubiquitous subatomic particles. The trick with neutrinos was finding ways to make them move in patterns, in effect to harness that great, potential mass into something that a physicist could find useful in explaining the origins of the universe.

Emphasis on potential. If only we could figure out how. Heaven knows no one else had.

Early on we collaborated with the Tow Center at Columbia on a study on reading habits, specifically, on how people discovered the kinds of long works of narrative nonfiction we published – and what increased the chances of those stories being discovered. We got 63 readers – close to evenly divided between men and women and ranging in age from 20 to 50 – to commit to keeping reading diaries for 21 days; in return everyone got a Kindle.

This is what they told us: people liked to read long stories; they read them at all times of the day, and every day of the week; they were most likely to read a story shared via email by someone they knew, and less so from social media; they were most likely to share stories on weekdays; and, they were most likely to read stories from a publication they knew.

Boiled down, this meant that the top of the digital pyramid were stories from, say, The New Yorker shared through email from a friend familiar with your tastes.

This created problems for us, beginning with the fact that we were not The New Yorker. Email was by far the most powerful tool for sharing but was difficult to scale, given its limited reach.

We did share our stories on Facebook and Twitter but the traffic was relatively modest – not surprising especially when a happy-talk Facebook rep made clear that if we wanted to increase our reach we could promote our posts – at a cost. Hundreds of dollars spent boosting posts made exactly no difference, perhaps because we were not spending thousands, or more.

We did ask each of our writers to send us a list of everyone they knew and we sent a mass bcc email, flagging their stories and asking people to share them.

Sometimes this worked. But not in any consistent way. What were we to do?

We knew that stories that found an audience did so through networks of people sharing them.

Maybe, we thought, we could build our own.

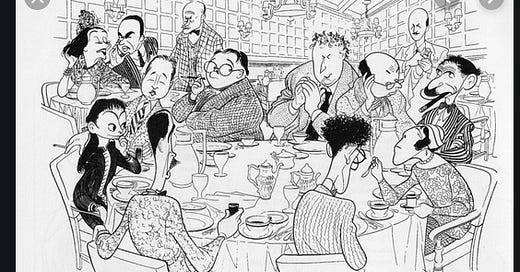

Here I need to take a step back, to a time before we launched, when the innocence I wrote about last week was captured in this illustration.

For those of a certain age – read: older – there are few more romantic literary images than this depiction of the “Algonquin Roundtable” by Al Hirschfeld. Here were famous-at-the-time-not-so-much-anymore literary sorts – Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woolcott – who for years met for lunch at a midtown Manhattan hotel where, legend had it, they said a lot of witty things.

This was the ultimate high school cool kids table, and when I showed it to writer friends they’d smile and, like me, think how much fun it would have been to be invited to sit in.

That is what we had wanted to create, absent the snark and practical jokes. We wanted to establish a circle where writers could gather – albeit virtually – to enjoy the company of one another, and in doing so resolve the loneliness that can feel so much a part of the writing life.

Hence, the name: the BIG Roundtable. I got permission to use the image and in our original website displayed it at the top, as if to say, This is who we are.

Our roundtable, however, would differ in one, essential way: its members would not think of themselves as the “the vicious circle” as the Algonquin’s did – you never wanted to get on Dorothy Parker’s bad side – but instead as an ever-widening collection of writers committed to helping one another. Especially by sharing each others’ stories.

A network built on mutual generosity.

Simple, yes?

Alas, as Hemingway – another writer from another age – wrote at the end of The Sun Also Rises – “isn’t it pretty to think so.”

I associated networks with the ones with which I was most familiar, beginning with the one at the center of my own family. My father came from a large, immigrant family with many, many aunts, uncles and cousins. At the center sat my grandmother who made it her business to keep this disparate group of people connected, even if they did not all particularly like each other. She did this with the telephone, which she took to every Saturday night after the end of the Sabbath and began calling her sisters, brothers, nieces and nephews, seemingly just to check in but really to ensure that as the new week began the network she worked so hard to cultivate would endure.

And then, when she was quite old but still very much in command, my grandmother died. Hundreds attended her funeral. The following year my uncle, her son-in-law, died. Maybe fifty people showed up.

With my grandmother’s death, the network dissolved, seemingly overnight. All the otherwise tenuous connections between people associated only by lineage evaporated. The strong bonds, the deep connections my grandmother may have wished for, turned out to be anything but. And like virtually all networks, it vanished.

Networks are a wonder to behold but almost impossible to predict. Think: you are at a baseball game and rhythmic clapping begins. Suddenly tens of thousands of people are clapping all at once. Then, an inning later, at a similarly dramatic moment in the game, you start to clap, in effect to launch your own network. Maybe the friend sitting next to you claps and maybe the person sitting behind you joins in. But no one else does. And you think: it worked an inning earlier for someone else, why not for me?

The answer is that nobody knows.

What we do know is that networks succeed when weak connections between people get stronger, strong enough to connect with others and by extension their networks. This is known as virality. My grandmother’s network succeeded because, by force of will and guilt, she made otherwise weak connections strong. But, as it turned out, they remained strong – and the network existed – only as long as she worked to ensure that that happened, one phone call reminder at a time.

This begged the question: could we create a mechanism for sustaining a network built on stories? Could we, in effect, replicate at scale the model of the irrepressible Tzipi Shapiro? Could we find a way to keep the bonds between our imagined network of writers intact story after story – just as my grandmother did week after week?

To do so we’d have to enlist a band of writers, and from them expand into an ever wider circle of people willing to share stories – often by people to whom they were connected by membership in the same organization.

In theory it made sense. But then again, in theory I could see how my grandmother might have believed that the many relatives on the other end of the phone shared her desire for a close-knit family.

My uncle once told me how, after extricating himself from the weekly check-in call from my grandmother, my aunt would look at the hang-dog look on his face and say, “that was your Aunt Tzipi wasn’t it?”

Maybe, I would slowly come to see, I was slipping into being her, forgetting how my beleaguered uncle felt.

Next week: if not our own network maybe we piggyback on someone else’s

* * *

If you have a question, a problem in your work, if you are feeling lost, stuck, confused, at sea, searching, grappling, or baffled, email me at Michaelshapiro808@gmail.com and tell me what you’re confronting and what help you need.

It is seldom, if ever, the case that one student’s problem or question is their’s alone.

Please indicate if you want to remain anonymous, have your name or just first name included. I will include the question and then answer it as best I can.

* * *

Nothing good ever came from writers punishing themselves. We know writing is hard. We’re here to show that it doesn’t have to be torture