Chapter 184: Long Ago and Like Yesterday, Too

It's good to be back. It is also good to have had what all writers need but which we too seldom are allowed, or allow ourselves: time to step away and hopefully see our work more clearly and fully.

I'd hoped that the distance I gave myself over the summer would grant me that clarity. But instead, what wisdom I gained did not come with time. In fact, it came only this week, with news of the death of an old friend.

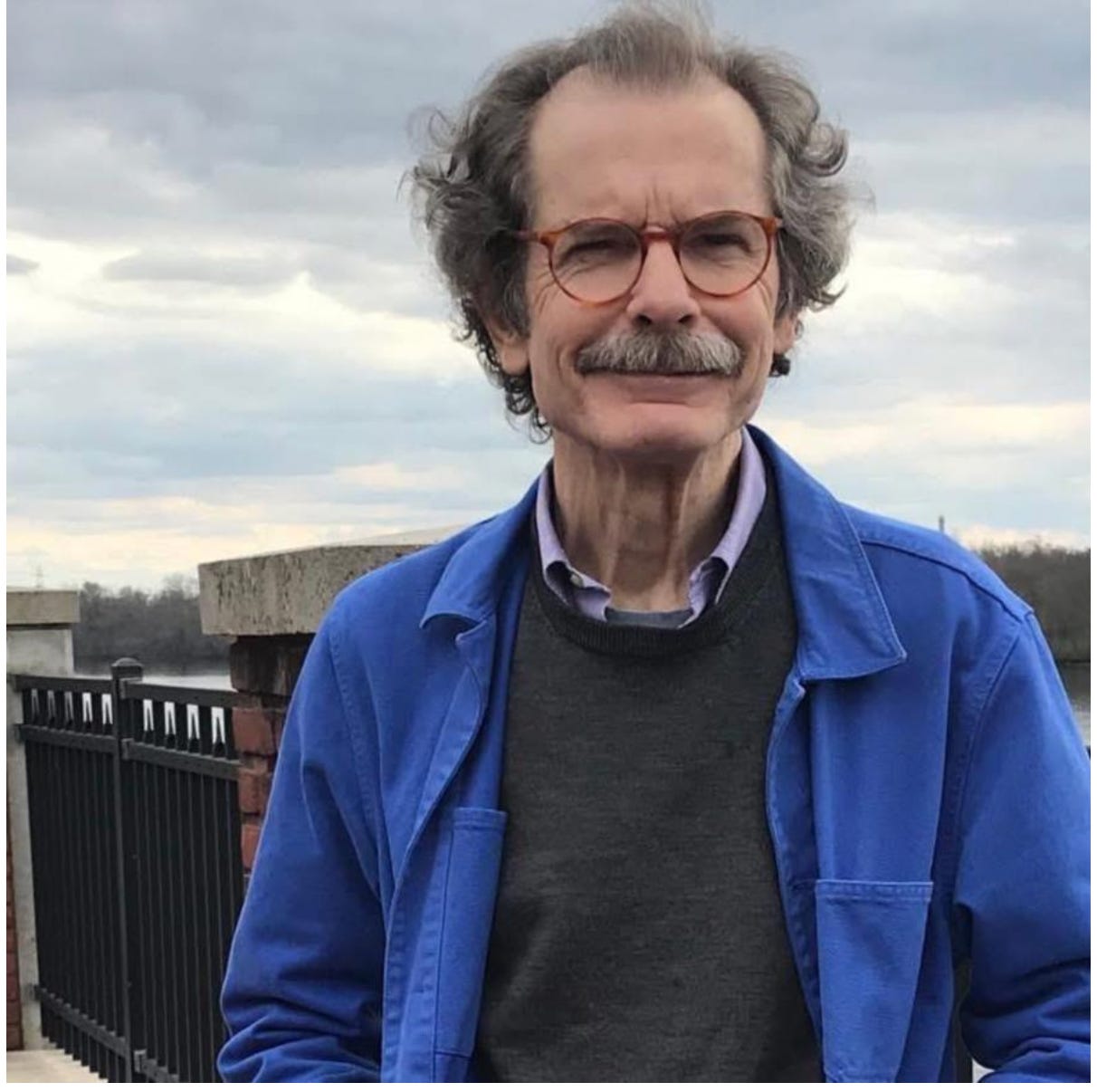

Paul Colford was 71. He was, professionally speaking, a throwback – for decades a big city newspaper reporter, at Newsday and later at what was once the nation's most widely read paper, The New York Daily News.

The work, especially at the tabloids where Paul thrived, was built on speed, adrenaline and competition. It did not leave space for reflection, not when the clock was ticking down to deadline and the city editor was breathing down your neck.

But then came a moment well along in Paul's long and distinguished career when he needed to pause, and do what reporters like him were conditioned never to do: turn back, slow down, and look inward.

In Paul's case that meant going back decades, to the summer after he graduated from high school, to a road trip with three friends, one of whom did not come back.

Because I spend so much time with students, trying to help them find their ways through their stories and to themselves as writers, I need to remind myself that the struggle to write is not limited to the young.

With the years come more skills with which we can better do our work. But those skills do not always prepare us for stories that, on the surface, look familiar but that can be altogether new, unsettling, and sometimes frightening.

Paul had written thousands of stories, and two books. He was as gifted a storyteller as I knew. But there was a story that lingered, unexplored and untold. It began when he and his friends Peter, Charlie and Pat, set off in Charlie's mom's Buick Special for a road trip. They felt like Jack Kerouac.

They headed north. They stopped at Dartmouth, where Charlie would begin college that fall – Paul and Pat would be staying close to home, at St. Peter's College in Jersey City – and then to Vermont. They stopped at an idyllic spot called Baker Pond. Paul, too tired to swim, stayed behind.

He had drifted off only to wake up and see Peter coming to him. He said, "Pat's hurt."

"There was one story I put off reporting even though it entered my thoughts more and more often in recent years: the story of Pat’s drowning," Paul wrote. "I couldn’t quite crack it and was slow to try. The easy cop-out was that the daily newspaper stories got in the way. But the deeper reason for my unwillingness to turn over rocks and sift through memory was that the inquiry would require some hard questions of myself, as well as Peter and Charlie — two friends whose actions that day had become all too comfortably fixed in my mind and, for all I knew, in theirs. My friends seemed entitled, after all these years, to a permanent reprieve from whatever summons my questions might represent. It was easier not to ask."

Until, thirty years later, when he felt the time had come.

"The past is never dead," wrote William Faulkner. "It's not even past." So it was with the story of Pat's drowning. The memories – the bits and pieces of an event never quite buried, began to emerge, as vividly as if all this had happened the day before. The music they listened to as they drove. The shape of Baker Pond. The peninsula that jutted into the water. The futile attempts to revive Pat.

Paul understood that he would have to return to Baker Pond, where he discovered that almost nothing had changed. "I wasn't prepared for that," he told me in a podcast we recorded about what it took to report and tell his story, When We Stopped at the Water. "I wasn't prepared for it to be so similar."

He performed the tasks reporters do: he re-traced his steps. He found the police and Pat's death certificate. "The documents were like maps to a buried past," he wrote. "They pointed the way back with their unexpected richness of detail, while leaving larger truths yet to be discovered." Then he called Charlie and Peter.

They had remained close friends; these were not strangers whom Paul called which, as anyone who has ever interviewed a loved one can attest, made the work much more difficult.

It was not as if they were reluctant to talk. They had talked about Pat from time to time over the years, mostly recalling moments that made them laugh. This was different because now Paul was sitting across from them, pen and notebook in hand, asking about an event that had shaped each of their lives.

At first the interviews skirted along the surface. But the more they talked, he said, the more "I found out things I did not know in the months that followed the accident.

"They wished to express their own feelings about what happened. To say it was cathartic would be a simplistic description."

The writing itself felt liberating, after so many years churning out daily dispatches. But the writing, like the reporting, triggered its own set of memories – looking at a photograph, and not so much remembering the day, but, as he put it "being transported."

"Time," Paul wrote of his return to Baker Pond, "had sanded away the four-foot bluff and left a long, manageable slope to the water’s edge, now mere inches off. When I turned around at this spot, I could see again the doctor and the cops emerging from the growth, finding us too late to matter.

"It’s the place where Pat died, but also where he lived and laughed. I studied every inch again and absorbed its lonely beauty."

Then, "Sad? A little. But more wistful about the road of friendship that led us here and the time since past.

"The paradox, I see only now, is that what happened at Baker Pond has become central to the friendships that abide the tragedy — friendships that this middle-aged man allowed to become diminished by neglect while hungry for contact. Friendships that seem clearer, and more precious, since my going back.

"Before heading home, I returned to the pond briefly in the cold morning. Under a brighter sun that lit up the peninsula through gaps between blooming trees, I realized I would probably never return. It’s unimportant now, for the place is neither tomb nor memorial.

The cool water refreshes, at last."

* * *

Over the past few months I've been working with a team of terrific journalists on a new project. It's called CollegeWatch. It's a free weekly newsletter covering the Trump Administration's assault on higher education.

Rather than trying to cover every event in a story that feels so relentless we instead will offer a story a week.

Many thanks.